Boredom, isolation and a burglar have turned out to be handmaidens of creativity for me.

I was in Poole in Dorset for the first of the lockdowns in my late mother’s rambling but decrepit home. It had lately been relieved of its television set by a local hoodlum. I had gone from attending glittering first nights in the West End as The New European’s theatre critic to assessing the performance of a mouse that I watched each night, as I ate my carefully-rationed dinner, on its perambulations around the kitchen floor.

It was a kind of prison for me, but periods of incarceration have often resulted in interesting literature, for good or ill. Ask Oscar Wilde or Adolf Hitler. A call out of the blue one day from Malcolm Turner of the publishers SunRise got me working on a book. I may have felt I’d ceased to be a household name even in my own household, but, cheeringly, he said he’d been aware of me as a presence on Twitter and on the BBC before my views on Brexit had turned me in middle-age into an unlikely Pringle-jumpered political dissident.

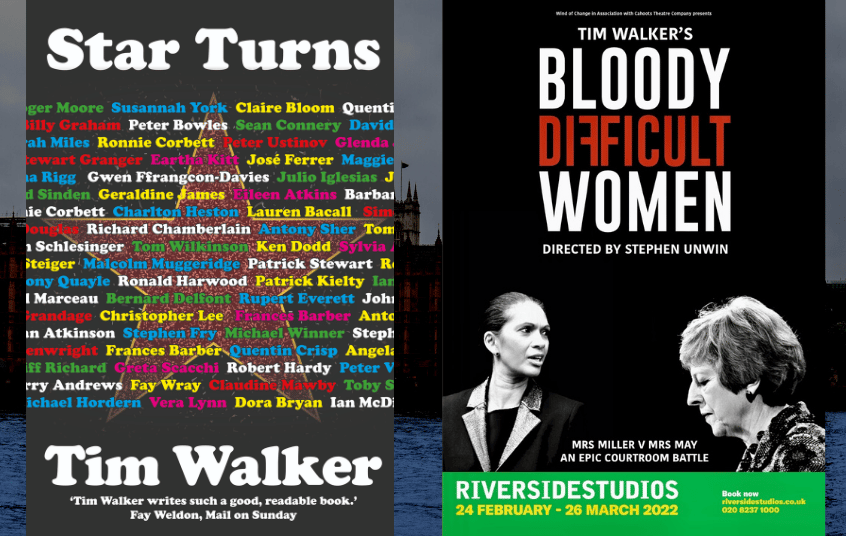

Malcolm had his heart set on a political book, but, being a great believer in economy of effort, I suggested instead turning a popular series called Star Turns that I was writing for The New European – my way of filling my old theatre slot – into an illustrated volume. This proved to be a much more arduous endeavour than I’d imagined because Malcolm needed at least 70 stars and I’d only written, until that point, of my encounters with about half that number so it was necessary to trawl through my old cuttings again. It’s funny how I could have completely forgotten about interviewing individuals like Charlton Heston and Kirk Douglas, but, then again, I’d found them both rather boring.

There was also on the back-burner a play I’d written called ‘Bloody Difficult Women’ that I’d assumed had gone the way of all flesh after its big opening night came and went in the June of that miserable year. Stephen Unwin, the distinguished director we’d got on board, had, however, become a friend, and, I think, knowing that I was someone who needed to be kept busy, decided this was the time to teach me how to become a bit more than a merely competent playwright. On innumerable Zoom meetings, this great man gave me free of charge the kind of tuition money could not buy. The play went through at least a thousand rewrites and I began to see in the words that were starting to appear on the page something really special beginning to emerge. I’ve said it once and I will say it again – there is no such thing as good writing, only good re-writing.

And so these endless pointless indeterminate days of lockdown began to take on a shape and a meaning for me. I got into a spartan new routine. Each morning I got up early, snuck down to the beach, and, rain or shine, swam to a buoy and back, burning off precisely 500 calories. Endorphins are the spur to creativity. Then it was getting stuck into the book, with the afternoons and evenings spent on making Stephen happy with the play, and, all the while, I kept the columns I wrote for The New European going, too, with occasional phone call interviews with politicians.

It’s funny how when there was so little to distract me, and after I’d got to know indolence of a kind I’d never before had to cope with, I was suddenly approaching writing with a vigour and enthusiasm I hadn’t really known since my first days on a local newspaper. Suddenly it all seemed to matter more than it ever had. It’s an extraordinary thing how much more we can all get done without the pressures of an office job and the day-to-day time-wasting tube-travelling morale-sapping tedium of living in a great metropolis.

The book has lately been published to an enthusiastic press and the play begins its run at the Riverside Studios in west London in February next year and obviously, I’m excited. In common with the vast majority of people, I went through some of the longest and most depressing days of my life during that long enforced period of nothingness. I got to know, too, all of the creatives involved in my play a lot better than I’d otherwise have done, including a brilliant young actor who was going to appear in it. He’d been hoping against hope that he’d get to have his big break on Broadway, but that opening came and went, too, during that time. He coped with it with remarkable good grace and fortitude. It was humbling to be made aware of quite what random things fame and success actually are, but we need, for all that, to keep striving. It’s what gives life meaning.

It left me all appreciating the wisdom of what Richard Nixon, of all people, had once observed: it’s only when we’ve been through the deepest valleys can we know how good it feels to stand on top of the highest mountains.

For more information about the book click here, or to find out more about Tim Walker’s play, click here.