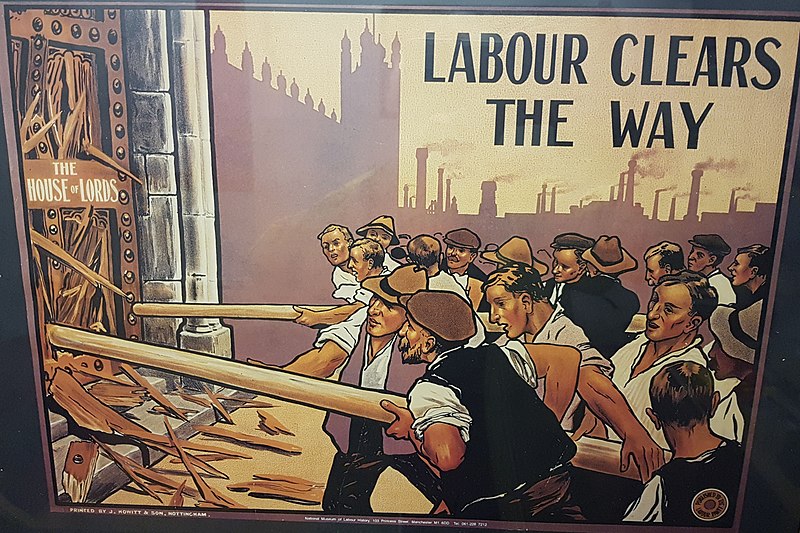

Over 2 weeks ago, Keir Starmer proposed significant constitutional reforms he would enact if he came to power. Most significantly, Starmer highlighted his plans to replace the House of Lords with a second elected Parliamentary chamber.

Starmer’s plans to abolish the House of Lords come as part of a wider constitutional project. His aim, as stated, is to improve the British public’s trust in politics.

“House of Lords reform is just one part of that … People have lost faith in the ability of politicians and politics to bring about change, that is why, as well as fixing our economy, we need to fix our politics.”

Keir Starmer speaking speaking to Labour MPs at a meeting in November

To achieve this, he appointed ex-Prime Minister Gordon Brown to create a broad constitutional review, with him recommending a radical devolution of power away from Westminster. This includes new tax powers for devolved governments and new local powers for enacting Parliamentary bills, among other things.

Expanding on his plans, Starmer claimed that people have lost faith in politics due to successive Prime Minister’s abuse of the British system.

This comes weeks after Boris Johnson’s resignation honours list was leaked in early November, revealing his plan to award ultra-loyalists and Conservative Party donors peerage status in the House of Lords. These include ex-culture secretary Nadine Dorries, one of Johnson’s most enduring supporters, and Carphone Warehouse co-founder and Conservative Party donor David Ross.

In a chat with Sky News on Monday, Starmer confirmed his plans to replace the House of Lords with a wholly elected second chamber in his first term of government. He said that this reform would be the biggest transfer of power out of Westminster that our country has ever seen, suggesting regional representatives would play a role in the second chamber.

Such a policy proposal is a big deal. The House of Lords is one of Britain’s most enduring political traditions, emerging as a distinct element of Parliament over 700 years ago.

So what does the House of Lords do?

The House of Lords acts to provide detailed scrutiny, and subsequent revision, of government legislation. This is deemed necessary for several reasons.

Primarily, MPs in the House of Commons do not have time to analyse the precise details of every government bill that passes. They may have constituency duties for example, among other commitments. As a result, bills can sail through the House of Commons with discrepancies in its wording and intent.

The fact that the Government also controls the timeline in the House of Commons means that it is effectively able to prevent MPs having a thorough read through proposed legislation before voting on and approving it.

Therefore, once the House of Commons votes on a bill, it gets sent to the House of Lords to be passed, blocked, or revised. The Lords will analyse proposed legislation line-by-line, and are able to suggest amendments throughout.

After this, the bill is sent back to the House of Commons for revision and so on. This is called Parliamentary ‘ping-pong’. However, The Lords cannot indefinitely block legislation, with the Commons able to force through legislation after 2 years.

Those in favour of the House of Lords highlight its ability to offer a level of scrutiny beyond what is possible in the House of Commons. Peers are usually experts, with very specific knowledge in a certain field. This means legislation is not merely rubber stamped by partisan MPs who are whipped into voting a certain way.

In essence, the House of Lords is a check on Government power. If the ruling party has a large Parliamentary majority, they can essentially pass anything they please within reason. Therefore, the House of Lords acts to neutralise potentially harmful or discriminatory legislation.

One example of this is the recent Nationality and Borders Bill which intends to send asylum seekers who land on British soil to Rwanda, in an attempt to dis-incentivise arriving to Britain as a refugee. The House of Lords were concerned over the ethics and legal status of such action, so have rejected and heavily amended this bill twice so far.

However, the House of Lords is controversial. Most notably due to its undemocratic nature

Peers are not elected by the people, or even by MPs, but the Prime Minister has the solo authority to nominate Peers to the House of Lords. Once a Peer enters the Lords, they are there for life. This arguably breaks all notions of democratic accountability and legitimacy.

Centralised patronage powers also leave the door open to corruption. There have been several scandals relating to the Prime Minister’s abuse of such powers. Most notable are the various ‘Cash for Honours’ scandals where a connection is found between political donations and the awarding of life peerages. Those peers have been dubbed ‘Tory’s Cronies’ during Blair’s premiership, and ‘Dave’s faves’ in the case of David Cameron.

The fact that Lords can also sit as Government Ministers adds to such concern. Conservative Peer Zac Goldsmith lost his seat as an MP in 2019 due to personal unpopularity within his constituency, but he still holds the role as Minister of State for Energy, Climate and Environment. It seems undemocratic to allow unelected, or even deposed MPs, to hold office in central Government.

Several controversial peerages which hit the headlines recently include Evgeny Lebedev, son of an ex-KGB agent, appointed by Boris Johnson. British Intelligence services supposedly raised opposition to his peerage on grounds of national security, but it was pushed through regardless.

Even more recently, Liz Truss, after a failed 45-day tenure which crashed the UK economy, is said to be planning a resignation honours list. Clearly the appointment process as it stands is open to abuse.

Such concerns have traditionally seen the Labour Party taking a stance against the House of Lords. In fact, until the 1980s, the complete abolition of the Upper House was a consistent theme within their manifestos. However, reform to the second chamber is notoriously difficult to enact.

In the 1960s, Harold Wilson failed to implement plans which would have reduced the powers of peers to amend and delay legislation, especially among hereditary peers.

Tony Blair had more luck. He was able to reduce the number of hereditary peers in the House from 750 to 92 under his manifesto pledge and a super majority in the Commons. This was clearly a forwards step for reformists, but Brown’s plans to modernise the Upper House into an elected body never came to fruition.

This brings us back to Keir

Starmer’s call for an elected second chamber would be considered a huge constitutional overhaul. But whether it is practically feasible to complete such a reform within one Parliamentary term is another story.

Starmer’s sudden focus on the House of Lords could also be seen as a strategic decision on Labour’s behalf. Primarily, it may act to neutralise an increasingly vocal group of people, a lot of whom are from within his own party, who are calling for Britain’s electoral system to be replaced with a more proportional voting mechanism.

These calls seem to be coming from people who see the failure over the last decade as systemic to the political system we live in. Such a system is characterised by a two-party system, and the root cause of this is our voting system, First-Pass-the-Post.

Starmer has repeatedly opposed any move away from a First-Past-the-Post voting system towards Proportional Representation. He may just believe that his landmark constitutional overhaul of the House of Lords is enough to quell such increasing demands.

Proportional representation would usually prevent any party from achieving a Parliamentary majority in the Commons, including Labour. And as we know, Turkeys don’t vote for Christmas.

Only time will tell whether Starmer’s deflection works. The House of Lords is a notoriously change-resistant institution, so abolishing their very existence will be an eventful process to say the least.

However, if successful, it may prove fruitful to gain the trust of the British public, while also silencing calls for more fundamental, and potentially suicidal, constitutional changes.